Crossroads: A family portrait

by KATY CORNER, MARCH 2006

"I'm a printmaker," states Anthony Davies. "I've got it tattooed across my forehead." He goes on to say.

"Printmaking...is basically quite a boring medium," he says, and and thus proceeds according to a logic designed to keep himself - and his viewers - interested. He is continually looking to expand the reach of printmaking and to open out its potential. "I suppose what I am trying to do in my work a lot of the time is to reinvent myself...it's a mass of contradictions."

Davies works systematically with a cast of characters from his immediate environment. Over the years, hundreds of strangers have unwittingly served as models. He also gathers incidents of trauma from the media, distils the elements which disturb him from local and international events and works them out through his print series. Perhaps this provides partial catharsis; probably Davies is not looking for release. Disquiet is an ingredient in bearing witness. Davies doesn't push messages. He offers blunt images balanced by colour and design. Though he seeks innovation, the work is gimmick-free. Real life is startling enough, he seems to say.

"Printmaking...is basically quite a boring medium," he says, and and thus proceeds according to a logic designed to keep himself - and his viewers - interested. He is continually looking to expand the reach of printmaking and to open out its potential. "I suppose what I am trying to do in my work a lot of the time is to reinvent myself...it's a mass of contradictions."

Davies works systematically with a cast of characters from his immediate environment. Over the years, hundreds of strangers have unwittingly served as models. He also gathers incidents of trauma from the media, distils the elements which disturb him from local and international events and works them out through his print series. Perhaps this provides partial catharsis; probably Davies is not looking for release. Disquiet is an ingredient in bearing witness. Davies doesn't push messages. He offers blunt images balanced by colour and design. Though he seeks innovation, the work is gimmick-free. Real life is startling enough, he seems to say.

|

" Nobody has ever before asked the nuclear family to live all by itself in a box the way we do. With no relatives, no support, we've put it in an impossible situation."

- Margaret Mead |

Davies presses scenarios at us, stakes his claim. He seems to say, "Here, this relates to you and I'd like you to pay attention."

The overflow of concepts can become hallucinatory and for our benefit Davies places guide marks along strategic lines. He is occasionally a trickster, inserting for instance, giant hands to tempt our eyes away from a more easily digestible path. Guidelines turn hands into hills and we're lost and found in the tangle. He makes us work for our results. Over the last three years, Davies has worked in lithography: Twin Towers, Wanganui, screen prints: Camouflage: With Attitude and now woodcuts: Crossroads, A Family Portrait. With each, he brings a lifetime's knowledge of, and obsession with, printmaking to stretch the limits of what he has done before. |

Every medium has its own challenge and rewards. Each litho stone has its individual qualities to be reckoned with; in screenprinting, ink density becomes of prime concern. Woodcuts allow the surface to directly interject into the finished result. All of these processes are task heavy and require a degree of meticulous handling for precise results. That said, an artist of Davies' calibre and experience can also relax into intuition and it is here where the magic occurs.

Davies keeps interested by alternating mediums - from lithography to screenprint to woodcut. "It's a psychological ploy," he says. "It's all part of my armoury on completing work." He is ever on the lookout for new ways to present his work. He says, "Now I want to do something which is noticeable. It's the whole thing of visual impact."

The media provides Davies with an ever-changing arsenal of research material and stimulates his need for action. In 'Camouflage', newsmen and their apparatus infiltrated the prints, adding to the cacophony and fulfilling their own prophecies of destruction. In 'Crossroads', the media stays away. It's more important to Davies that we are personally affected by the characters depicted and touched by the stories we imagine for them.

Patterns emerge looking at Davies' work over time. He has so much to report and present to us that multiple stories must be presented at once. It is worth looking back to the beginning of my association with him. In 2003, 'Twin Towers, Wanganui' was a massive, flowing concept, made eerily prescient by the massive flooding which occurred soon after their completion. Davies acted as director as the swollen river pushed the viewer's emotions along. Scenes of devastation were rolled out and then resolved. Over the course of 32 prints, a frenetic dance of line and form was built, then saturated with colour. Scenes from reality were overtaken by Davies' imagination and reconstituted into a hyperreal, spine tingling ride.

Davies keeps interested by alternating mediums - from lithography to screenprint to woodcut. "It's a psychological ploy," he says. "It's all part of my armoury on completing work." He is ever on the lookout for new ways to present his work. He says, "Now I want to do something which is noticeable. It's the whole thing of visual impact."

The media provides Davies with an ever-changing arsenal of research material and stimulates his need for action. In 'Camouflage', newsmen and their apparatus infiltrated the prints, adding to the cacophony and fulfilling their own prophecies of destruction. In 'Crossroads', the media stays away. It's more important to Davies that we are personally affected by the characters depicted and touched by the stories we imagine for them.

Patterns emerge looking at Davies' work over time. He has so much to report and present to us that multiple stories must be presented at once. It is worth looking back to the beginning of my association with him. In 2003, 'Twin Towers, Wanganui' was a massive, flowing concept, made eerily prescient by the massive flooding which occurred soon after their completion. Davies acted as director as the swollen river pushed the viewer's emotions along. Scenes of devastation were rolled out and then resolved. Over the course of 32 prints, a frenetic dance of line and form was built, then saturated with colour. Scenes from reality were overtaken by Davies' imagination and reconstituted into a hyperreal, spine tingling ride.

|

The vision spiralled outwards in 2004 with 'Camouflage: With Attitude'. These screen prints were a triumph of intensity and excess. Davies wrestled discrete forms into a kind of temporary truce, a blink-and-you-miss-it meeting of horror and happiness. Clamouring voices and reaching gestures compelled the viewer into their world. The media invaded, becoming part of the sense of menace. Landscapes and historical scenes were buried beneath fractious insertions of disorder and upset.

Davies exhibited the initial 10 prints of 'Camouflage', and has since added five more. These latter works seem to form a bridge between the full on clamour of their predecessors and what flows in 'Crossroads'. They take major elements from the first 10 works and distil them into a more focussed landscape of issues. They appear calmer, yet with less visual overload, their subjects are more clearly defined. |

"In each family a story is playing itself out, and each family's story embodies its hope and despair."

- Auguste Napier |

This doesn't mean Davies is simplifying things for the viewer. In 'Crossroads', deceptively simple structure, each segment offers a stark summation for us to decipher. Red inserts act as anchors or guideposts, their irregular shapes skewing an overall order. These relate to the larger black and white shapes but are deliberately set apart. Acting like freeze frames or storyboards, they point to an instant in time which will soon enough be overtaken.

With "Crossroads' in 2006, Davies has pared the elements back even further. The essentials of composition have been weighed and judged; anything extraneous is discarded. The visual cacophony is now streamlined into a purer form. Conflicting voices still make their presence known, but Davies' insights are more clearly delivered.

With "Crossroads' in 2006, Davies has pared the elements back even further. The essentials of composition have been weighed and judged; anything extraneous is discarded. The visual cacophony is now streamlined into a purer form. Conflicting voices still make their presence known, but Davies' insights are more clearly delivered.

Davies' representations of family fit certain preconceptions, but he compels us to add other factors into the mix. Reflecting complex issues, nothing is simple here. Davies says 'Crossroads' is about involving some sort of family. The narrative thing has always been there and always will be. It's from his min, but it is the idea of identity as an artist which challenges him even more. In basing a print series on 'family' he is exploring these issues. He says, "I want an identity. I want people to look at that figure and say 'oh, perhaps I know them'."

The concept of Family is a universal one, easy for the viewer to take on, yet individual reactions are impossible to predict. Family is being represented, and our natural curiosity takes over. We are compelled to see what kind of family is being depicted, if it matches our own experience. However, any illusions we have of Davies 'family' being user-friendly is shattered once we see where he is headed.

Instead of using traditional clichés of 'family' as a stable force, a kind of saving grace, Davies depicts it as also a minefield of tension, a war zone where people struggle against their tenuous ties. Notions of family unity and togetherness stand alongside the reality that families are where the hardest truths and lessons are learned.

Families are inviolable - or are they? Outside forces wrench them apart, internal disputes wreak havoc. Some pieces are rescued and others have the constitution to adapt; the whole is constantly being eroded and mutating in a never-ending cycle. 'Crossroads' shows family as a fractured jigsaw. Pieces are missing, others are warped; it is an awkward fit.

When displayed in crossroads form, 'Crossroads' aims to produce a striking visual impact. This series is saturated with a powerful spiritual element. It's figures can be seen as tragic icons, caught in passion, uplifted by spirit. The characters are taken over, seemingly by forces out of their control. They display emotions which are within the range of ordinary experience, yet Davies' placement makes sparks fly.

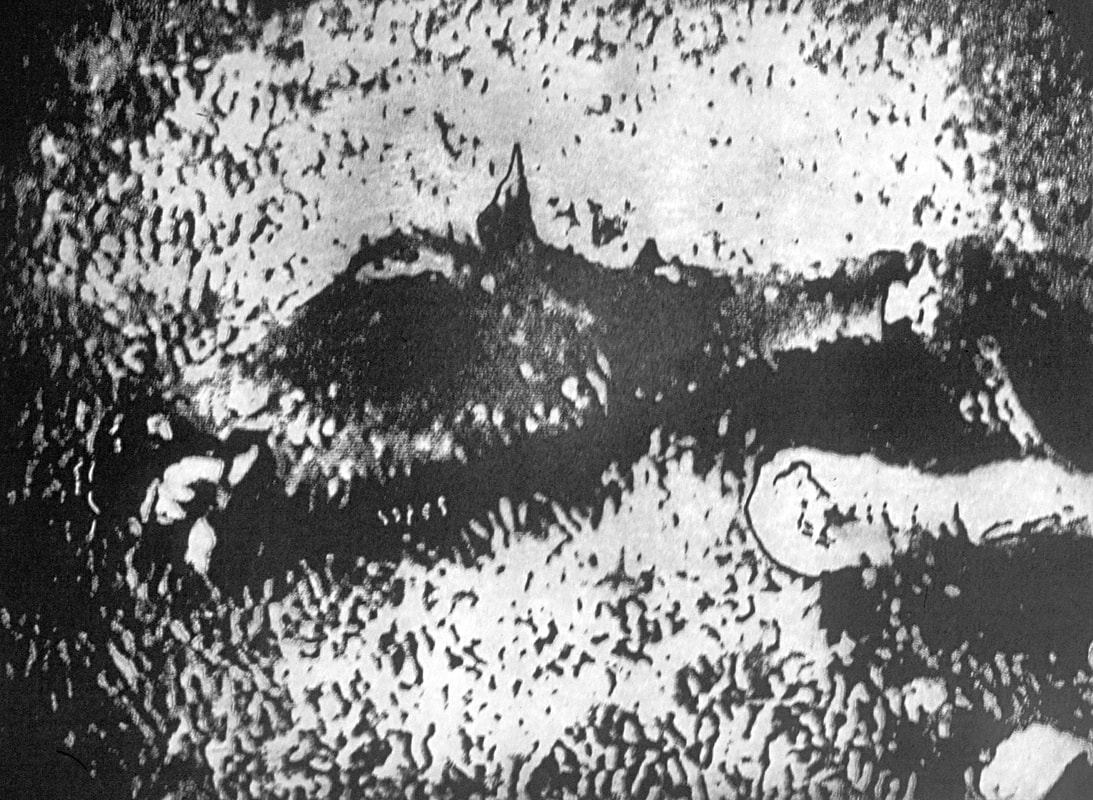

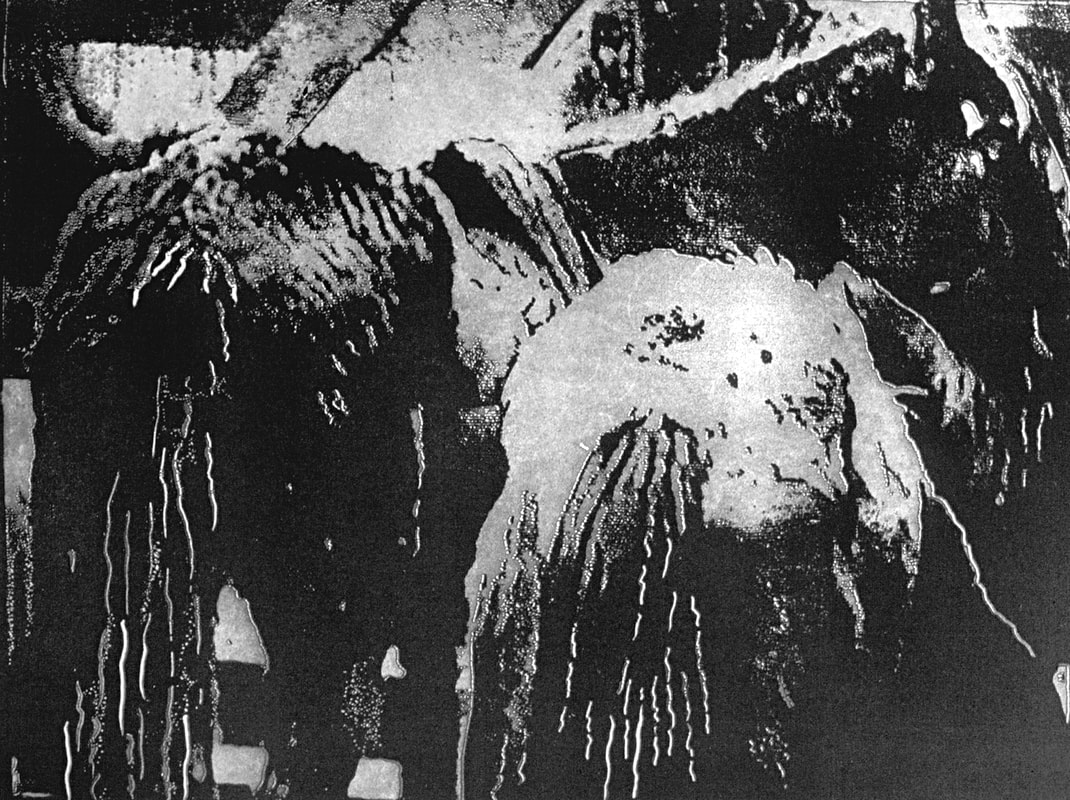

Davies' use of wood invokes ideas of regeneration, history and cycles perpetuating and being perpetrated. The grain of the wood anchors each distinct figure. Rings from knot holes act like whirlpools to herald danger and signify the passing of time. The eye is jettisoned from one section to another. White figures emerging from a grained black/white surface are loosely corralled by floating red asymmetrical shapes.

Structurally, these red inserts and the recurring deep criss-crosses bring figures to the fore. There is movement suggested, as in musical notation or a diagram of dance steps. Figures emerge from the dark backgrounds, some stoic, others corrupt, all damaged to some degree. Cycles come to momentary and momentous halt - in the scenes of funeral, plan and car crashes - then pick up and move on a bit more battle scarred.

The concept of Family is a universal one, easy for the viewer to take on, yet individual reactions are impossible to predict. Family is being represented, and our natural curiosity takes over. We are compelled to see what kind of family is being depicted, if it matches our own experience. However, any illusions we have of Davies 'family' being user-friendly is shattered once we see where he is headed.

Instead of using traditional clichés of 'family' as a stable force, a kind of saving grace, Davies depicts it as also a minefield of tension, a war zone where people struggle against their tenuous ties. Notions of family unity and togetherness stand alongside the reality that families are where the hardest truths and lessons are learned.

Families are inviolable - or are they? Outside forces wrench them apart, internal disputes wreak havoc. Some pieces are rescued and others have the constitution to adapt; the whole is constantly being eroded and mutating in a never-ending cycle. 'Crossroads' shows family as a fractured jigsaw. Pieces are missing, others are warped; it is an awkward fit.

When displayed in crossroads form, 'Crossroads' aims to produce a striking visual impact. This series is saturated with a powerful spiritual element. It's figures can be seen as tragic icons, caught in passion, uplifted by spirit. The characters are taken over, seemingly by forces out of their control. They display emotions which are within the range of ordinary experience, yet Davies' placement makes sparks fly.

Davies' use of wood invokes ideas of regeneration, history and cycles perpetuating and being perpetrated. The grain of the wood anchors each distinct figure. Rings from knot holes act like whirlpools to herald danger and signify the passing of time. The eye is jettisoned from one section to another. White figures emerging from a grained black/white surface are loosely corralled by floating red asymmetrical shapes.

Structurally, these red inserts and the recurring deep criss-crosses bring figures to the fore. There is movement suggested, as in musical notation or a diagram of dance steps. Figures emerge from the dark backgrounds, some stoic, others corrupt, all damaged to some degree. Cycles come to momentary and momentous halt - in the scenes of funeral, plan and car crashes - then pick up and move on a bit more battle scarred.

* * * * *

Counting Down the Cross

|

If we look at MOTHER (Print #1), Davies has encapsulated her in a red box. She rests sedate in an armchair, ankles neatly crossed in slippers, hands clasped. This is the universal Mother of our wishful thinking. She waits, outwardly unperturbed, to offer unconditional love. She is not safe, though: marks are stripped into the wood, spreading outwards into the black and white arena where dance lurks. Her male offspring are loose; a mokoed head roars, its brow circled with sharp angles of graffiti like a barbed wire restraint. A second figure in sunnies clenches his fist; it's up for grabs whether he's cheering rugby, urging on a gang battle, or chanting 'Enough is enough'. There is primal power in these attitudes, and it's easy to imagine the carving tool used as a way to express fury. Davies leaves it to each viewer's experience as to whether this shows malevolent or high spirited male behaviour. As asides, Davies inserts a floating shape like a can's ring-pull or jacket's zipper. Scroll embellishments also appear, like talismans. At the base of the cross appears FATHER (#12). Tending to 'read' the vivid red box first, I see a preoccupied figure. He is trudging, intent on placing one foot before the other, with his half-furled umbrella trailing behind. He wears good clothes and hat, responsibility is wearing on him. Pointed score marks lock him in tightly. The larger section shows a proud aspect. His hat is defined by two simple shapes. Great energy and a large tool swoop into the wood to score a crude halo over his steady gaze. Tribal markings are inscribed on his face, perhaps suggesting rites of passage which a father inevitably earns. Again a protective scroll hovers over his figure.

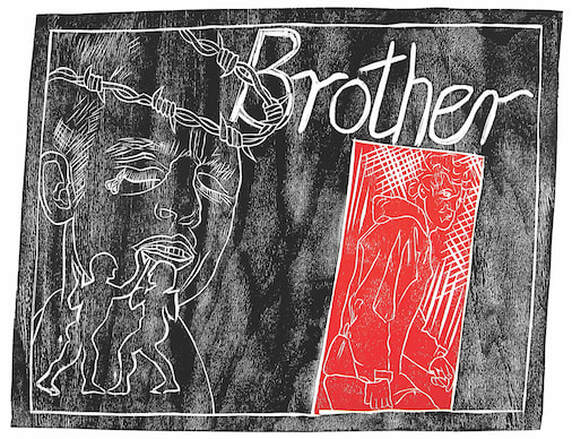

BROTHER (#3) occupies the far left position of the cross. Within its red rectangle, a boy in his ubiquitous hoodie lingers lost in adolescence. He is alert, in motion, hyped for action. In the main frame, appearing like graffiti, two figures are deeply scored which could be dancing or fighting. They invade the space of the largest figure who wears a barbed wire crown. His eyes are shut and anguished tears are displayed like prison tattoos. The wood grain works particularly well here to illustrate a flow of trouble.

Opposite at right, SISTER (#9) strides out in her electronic armour. Clothing wrapped around puppy fat like a cocoon, fists jamming headphones to ears, she's going her own way. Sex is glorified in the rippling, urgent lines of a couple. The female is receptive, awakening to it, curious. In the underlying form, she adopts sunglasses and smokes with nonchalance. Head back, she radiates the smugness self-confidence of youth. The wood's grain is explosive; to tales effort to decipher this print and it's warring attitudes. All is in flux.

|

In between the extremities of Davies' cross, lie people and events revolving around and relating to the core family members.

|

Below MOTHER in print #2, we see breakdancers etched in limber lines into the wood. A headphoned youth merges into the background. Testosterone and Cupid revolves around a girl who is nonchalant, smoking, posing, perhaps pregnant. She holds power over the loose cannon energy of the youths. This is the most difficult print to read. The grain interferes and threatens to take over surface, like acid etched a little long.

|

Print #4 sits next to BROTHER at the left hand side of the cross. Drama erupts in a red container with a broken plane in a suburban garden. The impact of crash is apparent in shaking lines. There is conflict between the regular surface and the violence of the red insert. The main figure is older and wearing a worker's cap. Despite his weary, thousand-mile stare, it's a sublime image.

|

Next to the centre, #5 features an older man carrying a bowl with scalloped edges, filled with provisions. In the red insert, young pallbearers move their burden from a church. They wear gumboots and jandals and are overseen by pylons on the ridge of hills.

|

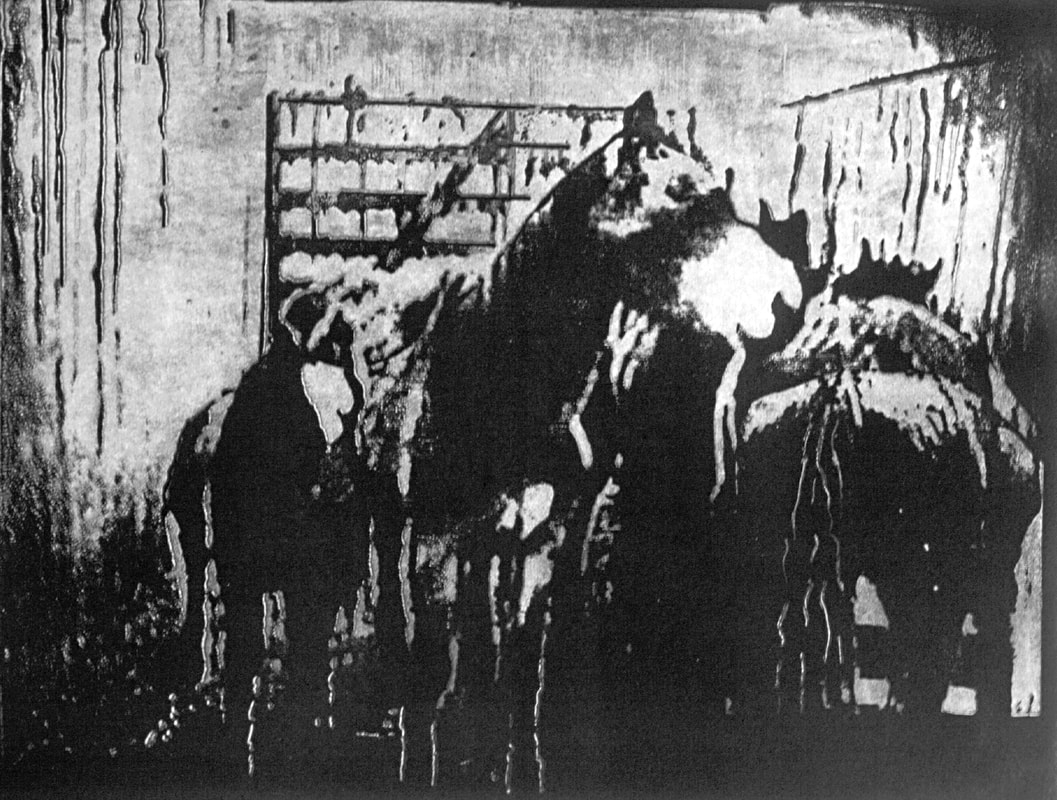

The central print, #6 is the print which to me most closely represent contentment. A horse and foal graze, corralled in red, alongside a house, boat and trailer. An elderly woman wears pearls and a warm coat. She is indescribable, as contained as her perm, hands clasped. Is she grieving, or is this suburban idyll her paradise on earth?

|

|

With #7 we enter dangerous territory. Suburban space is invaded by a car wrapped around a tree, or is it just a car, bonnet up, waiting repairs? Colour leaks from the white border of the red section. Outside, a youth adjusts his hoodie, face a blank mask save for the marking of a jagged eye socket. Is he a survivor, a perpetrator walking, shocked, away from the scene?

|

Alongside SISTER is #8, another benevolent scene, featuring an oblivious sow. A gumbooted, beanie-wearing man carefully bears gifts. This is a scene of plenty and rural domesticity. A stalwart old man leans on his panel his hat is part of him, his eyes are sightless.

|

Moving down to the centre of the cross, #10 shakes things up with it's young woman on a walker. We need to double take, coming across the disheveled man in a beanie. Predatory outlines give a nightmarish quality, and a disabled, cast off bike lays out the menace of accident and injury.

|

Stationed right above FATHER, #11 shows us a chilly, huddled sleeper protected within a magic circle of deeply scored, sharply pointed lances. Outside this red nest benevolence issues from a smiling woman wearing a lei of tropical flowers. Etched over her face is a silhouette in high heels, jaunty. At the base of the cross, FATHER supports the weight.

|

* * * * *

Davies considered calling this series 'The Ballad of Brunswick Park' after an area where he exercises his Dalmatians. As a watcher, these Wanganui walks allow him to observe and store data for future use. Davies is grimly fascinated with the human condition. By dwelling on the murkier aspects, he takes risks. He doesn't seem to have developed an immunity, nor does he take refuge in cynicism. Investigating the dark side leaves him vulnerable, but it's a necessary compulsion.

Davies says "I've never thought of art as being a particularly nice thing. People who write, or film makers - it doesn't exactly make for peace of mind. Perhaps that's the cross you carry. I mean, we all go through life believing in different things, or having an interest, a curiosity."

Davies says "I've never thought of art as being a particularly nice thing. People who write, or film makers - it doesn't exactly make for peace of mind. Perhaps that's the cross you carry. I mean, we all go through life believing in different things, or having an interest, a curiosity."