I PRINT THEREFORE I AM: Anthony Davies PRINTMAKER

by ELIZABEth RANKIN - June 2007

There is paradox inherent in the process of printmaking when it acts as a vehicle of social and political commentary. The very nature of the print facilitates the distribution of commentary, yet also intrudes upon the directness of the description and reception of the message, when technical issues may seem to dominate over content.

To expand the point – on the one hand, the possibility of producing editions of prints, which make feasible their dispersal, affords an ideal medium for spreading communication in visual form. In this, prints share the quality of multiplicity with printed texts and their ability to reach a wide audience. They often share with texts too the extension beyond a single episode, with the gathering of images into a narrative of sorts – as a series, or a portfolio of prints – which expands and reinforces the message.

On the other hand, the labour intensive nature of printmaking would seem to intervene between a direct reaction to social issues and their imaging, slowing the transferral of response into visual form. Printmaking is a process of delayed outcomes. Its practitioners have to translate their visions onto a matrix delimited by technical conventions, a particularly time-consuming method of making images, that requires the printmaker to be canny and crafty (in the original sense of the word) rather than spontaneously expressive. The mind of the artist shifts back and forward between concept and execution in an intricate interaction that makes drawing or painting seem relatively direct. Even to those entirely familiar with the idiosyncrasies of its processes and adept in its requisite skills, printmaking demands endless negotiation, not only throughout the production of the block or plate, but in the inking and printing itself. Each stage requires a range of decisions which, like those of the sculptor, are often not reversible. But, while the process may be a constraint, it can of course be highly productive – working ‘against the grain’ can promote innovative visual solutions.

These characteristics equally affect the reception of prints, and seem to compel a more contemplative reading, in contrast to the immediacy of, say, an expressive sketch or a hard-hitting caricature in a political tract. However much they might share similar intentions with such immediate forms, the fine detail described by engraved line in Hogarth’s prints, or the delicate tonal effects of aquatint in Goya’s etchings, for example, provide a mediating distance between a raw response to social ills and their recording through the medium of the print. The intricacy of the surface in a fine print may lure the viewer into a scrutiny of process – paralleling the way it must necessarily preoccupy the printmaker – and thus to some extent ameliorate the directness of the comment. But, by the same token, lengthier contemplation accommodates shifts in focus between process and content, and allows the meaning to develop at a more potent, albeit subtler, level than the immediate gratification of a relatively crude caricature.

For much of his career, Anthony Davies has worked in the tradition of the British print. There are affinities with the serial commentaries of a Hogarth (even to the point of an exhibition of works of 1979-85 being titled A Rake’s Progress) and also with the exaggerated stylisations of a Gillray or a Rowlandson, albeit overlaid with the more radical distortions of twentieth-century commentators such as Grosz and Dix. The underclasses of city life, urban decay, and social and political violence provide his most common iconography. Davies adroitly manipulates printmaking techniques to serve his purposes, finding ways to prevent the alluring alchemy of process from intruding on the impact of content. Rather, the process carries the meaning. He does not limit himself to any one technique, but explores the signifying potential of the medium across the full range of intaglio, relief and planar processes.

These paragraphs, which I wrote in 2003 to accompany Anthony Davies’ series of drawings and lithographs, Blood Sweat and Oil, remain a useful starting point for a consideration of his prints, whatever their subject matter. The exacting work ethic of printmaking and the obsessively repetitive requirements for producing editions seem to match Davies’ persona: he is (perversely) drawn to printmaking because it is so time consuming, so complex its production and reception, almost in contradiction of its democratic possibilities. As he remarked recently to Katy Corner, ‘I’m a printmaker. … I’ve got it tattooed across my forehead. But Davies’ single-mindedness does not manifest in his specialisation in a single process or even a consistent style. He exploits the versatility of printmaking as a multi-tongued visual language.

This is a quality that Davies shares with many contemporary artists who have chosen to work in the ‘expanded field’ of printmaking. No longer satisfied with the myopic focus of traditional fine prints, they investigate the potential of the medium to create complex post-modern statements, often going beyond the established processes of printmaking to incorporate photographic and digital forms of reproduction, and subverting tradition even further with the incorporation of different forms of mark making, collage and construction. Indeed it stretches definition beyond credibility to refer to some of these works as prints at all: it seems more appropriate simply to say that printmaking techniques have formed a part of the production of such mixed media art. While Davies too produces multi-media works, he remains committed to the print matrix and a conventional paper support, preferring to combine different processes or unusual applications of them than to transgress the parameters of his chosen medium. He also avoids digitally generated forms, although he incorporates photographic sources in his prints, and occasionally employs Xerox facilities to constitute his images.

The self-imposed complexity of Davies’ practice is tellingly exemplified in the first major series of prints completed after he had settled in New Zealand in 1998 (or one might say series of series since there are a number of separately titled sets). Their subject matter focuses on the landscape, paying homage to God’s Country, as he called an early sequence – albeit with an ironic edge. Ed Hanfling has eloquently explored Davies’ relationship to the conventions of New Zealand landscape. My concern here is rather with the way the making of his prints intersects with their meaning. More ‘artful’ than the prints he had been making in England and Ireland, these mixed-media works, which combine relief and screenprinting, were perhaps intended to establish his status as a definitively contemporary printmaker in a new terrain.

To expand the point – on the one hand, the possibility of producing editions of prints, which make feasible their dispersal, affords an ideal medium for spreading communication in visual form. In this, prints share the quality of multiplicity with printed texts and their ability to reach a wide audience. They often share with texts too the extension beyond a single episode, with the gathering of images into a narrative of sorts – as a series, or a portfolio of prints – which expands and reinforces the message.

On the other hand, the labour intensive nature of printmaking would seem to intervene between a direct reaction to social issues and their imaging, slowing the transferral of response into visual form. Printmaking is a process of delayed outcomes. Its practitioners have to translate their visions onto a matrix delimited by technical conventions, a particularly time-consuming method of making images, that requires the printmaker to be canny and crafty (in the original sense of the word) rather than spontaneously expressive. The mind of the artist shifts back and forward between concept and execution in an intricate interaction that makes drawing or painting seem relatively direct. Even to those entirely familiar with the idiosyncrasies of its processes and adept in its requisite skills, printmaking demands endless negotiation, not only throughout the production of the block or plate, but in the inking and printing itself. Each stage requires a range of decisions which, like those of the sculptor, are often not reversible. But, while the process may be a constraint, it can of course be highly productive – working ‘against the grain’ can promote innovative visual solutions.

These characteristics equally affect the reception of prints, and seem to compel a more contemplative reading, in contrast to the immediacy of, say, an expressive sketch or a hard-hitting caricature in a political tract. However much they might share similar intentions with such immediate forms, the fine detail described by engraved line in Hogarth’s prints, or the delicate tonal effects of aquatint in Goya’s etchings, for example, provide a mediating distance between a raw response to social ills and their recording through the medium of the print. The intricacy of the surface in a fine print may lure the viewer into a scrutiny of process – paralleling the way it must necessarily preoccupy the printmaker – and thus to some extent ameliorate the directness of the comment. But, by the same token, lengthier contemplation accommodates shifts in focus between process and content, and allows the meaning to develop at a more potent, albeit subtler, level than the immediate gratification of a relatively crude caricature.

For much of his career, Anthony Davies has worked in the tradition of the British print. There are affinities with the serial commentaries of a Hogarth (even to the point of an exhibition of works of 1979-85 being titled A Rake’s Progress) and also with the exaggerated stylisations of a Gillray or a Rowlandson, albeit overlaid with the more radical distortions of twentieth-century commentators such as Grosz and Dix. The underclasses of city life, urban decay, and social and political violence provide his most common iconography. Davies adroitly manipulates printmaking techniques to serve his purposes, finding ways to prevent the alluring alchemy of process from intruding on the impact of content. Rather, the process carries the meaning. He does not limit himself to any one technique, but explores the signifying potential of the medium across the full range of intaglio, relief and planar processes.

These paragraphs, which I wrote in 2003 to accompany Anthony Davies’ series of drawings and lithographs, Blood Sweat and Oil, remain a useful starting point for a consideration of his prints, whatever their subject matter. The exacting work ethic of printmaking and the obsessively repetitive requirements for producing editions seem to match Davies’ persona: he is (perversely) drawn to printmaking because it is so time consuming, so complex its production and reception, almost in contradiction of its democratic possibilities. As he remarked recently to Katy Corner, ‘I’m a printmaker. … I’ve got it tattooed across my forehead. But Davies’ single-mindedness does not manifest in his specialisation in a single process or even a consistent style. He exploits the versatility of printmaking as a multi-tongued visual language.

This is a quality that Davies shares with many contemporary artists who have chosen to work in the ‘expanded field’ of printmaking. No longer satisfied with the myopic focus of traditional fine prints, they investigate the potential of the medium to create complex post-modern statements, often going beyond the established processes of printmaking to incorporate photographic and digital forms of reproduction, and subverting tradition even further with the incorporation of different forms of mark making, collage and construction. Indeed it stretches definition beyond credibility to refer to some of these works as prints at all: it seems more appropriate simply to say that printmaking techniques have formed a part of the production of such mixed media art. While Davies too produces multi-media works, he remains committed to the print matrix and a conventional paper support, preferring to combine different processes or unusual applications of them than to transgress the parameters of his chosen medium. He also avoids digitally generated forms, although he incorporates photographic sources in his prints, and occasionally employs Xerox facilities to constitute his images.

The self-imposed complexity of Davies’ practice is tellingly exemplified in the first major series of prints completed after he had settled in New Zealand in 1998 (or one might say series of series since there are a number of separately titled sets). Their subject matter focuses on the landscape, paying homage to God’s Country, as he called an early sequence – albeit with an ironic edge. Ed Hanfling has eloquently explored Davies’ relationship to the conventions of New Zealand landscape. My concern here is rather with the way the making of his prints intersects with their meaning. More ‘artful’ than the prints he had been making in England and Ireland, these mixed-media works, which combine relief and screenprinting, were perhaps intended to establish his status as a definitively contemporary printmaker in a new terrain.

|

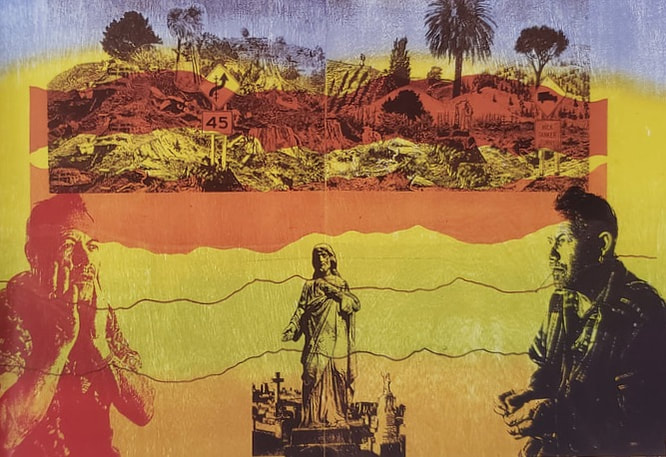

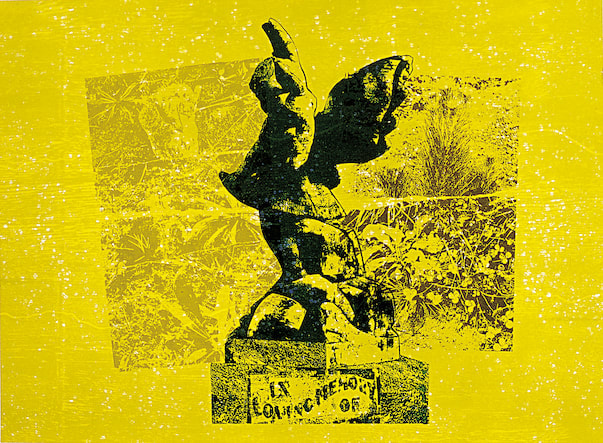

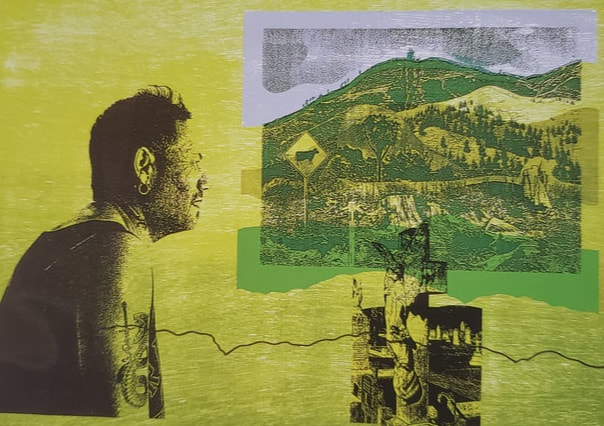

The series made between 2000 and 2001 – Journey Through the Takapau Plains; Waihi–In Memory Of; Winged Angels; Self Portrait–Out of Eden; and Epitaph for an Unknown Grave – are not editions, but autograph prints. For each a ground was provided by first printing the textured surface of an uncarved wooden block, usually inked up in a single colour, but sometimes more complexly graduated or overprinted. While acidic in tone, the choice of a predominantly greenish or ochre colour range connotes an out-of-doors natural setting, also evoked by the grain of the wood. The reference qualifies the photographic screenprinted images that are floated against it – segments of bush country, with tree stumps and road signs marking human incursions of various kinds; graveyard memorials acknowledging a different kind of possession of the land; and the artist’s self portrait which – unkempt, clad in singlet and baseball cap, lighting up a cigarette – could suggest surrogate bushman, urban invader or disinterested spectator. The ground acts as an important compositional device, establishing the picture plane and unifying the discrete monochromatic images, as do meandering horizontals of a different colour – minimal remnants of map making perhaps, or disengaged horizons.

|

Colour is also used more proactively. In the series Winged Angels, with more popular appeal perhaps than his customary subjects, the memorial figure with the repeated inscription ‘In Loving Memory’ is centred and printed in black, flanked by close-up views of flowers and plants. But the paired landscape fragments are set askew, breaking with the tectonic rectangle of the print, and are inked in different colour tones, sometimes unexpectedly hot oranges and ochres against a vivid background, creating a dissonance at odds with the melancholy charm of the subject matter. In Journey through the Takapau Plains, the single more distant landscape images are overprinted in undulating bands which spill beyond their borders and are tauntingly mismatched with the contours of the land – blues for the sky almost but not quite following the hilly horizon, greens breaking free of scenic details. Colour has an independent existence, unrestricted by form, and certainly not employed for descriptive ‘colouring in’. In these works it calls to mind the saccharine hues of hand-tinted photographs and poorly registered colour postcards. It makes overt a misplaced nostalgia for olden day rural scenes and country cemeteries, long since overtaken by decay or vandalism but fondly restored in memory. At the same time, it speaks of the reconstitution of images in art practice, of the elusive and allusive nature of representation.

An interesting counterpart to the use of colour in these works is found in the series Camouflage: With Attitude of 2004-05, which solely uses screenprinting. Again colour supplies a unifying ground, but it is quite differently conceived. Devised by using a Xerox machine to transfer camouflage patterns onto acetate material, then processed onto silkscreens photographically, the two-colour designs were printed in various configurations, sometimes the same pattern reversed, for example. The colours range from vivid vermilions and greens, through the more expected browns, olives and ochres of army gear, to delicate pastel blues. Usually the colours in each print are related hues, with overprinting creating additional tones, but sometimes there are unexpectedly clashing contrasts such as the lime green and pinkish orange of Print 4. It might be expected that such activated surfaces would dominate the prints and preclude the reading of other forms. But Davies mixed the coloured inks with a transparent base so that, while the camouflage patterns give continuity to the surface, they are relatively muted and rarely overwhelm the images that are printed over them. And their unifying function is a very necessary component, for the figurative elements are made up of seemingly random imagery, drawn with felt pen onto acetate sheets to create the subsequent screenprints of black line. They hover somewhere between the palimpsests of graffiti, the incessant repetitiveness of media images, and the repetitive rag bag of memory and dream – or is it nightmare?

The myriad drawings provoke the eye in their staccato congregation and shifts of scale. Only the ground holds them together, although in a provocative way, since the very idea of camouflage is to disguise rather than reveal. We find benign suburban and rural scenes cheek by jowl with confrontational images of violence, the dominant theme seemingly the icons of underclass urban culture – hoodies, hand gestures, tat slogans. Incongruously wedged amongst them are fleeting quotations of well-known artworks (I spotted the crest of Hokusai’s great wave of Kanagawa, an apocalyptic rider reminiscent of Northern European engravings, and linear hill contours culled from South Island landscapists). There are shifts of style too, from crudely bold outlines to finely stippled surfaces and intensive cross-hatching, with no obvious consistency in their application to different forms. In its deployment of multiple styles and motifs, Camouflage: With Attitude embodies a paradigmatic act of appropriation.

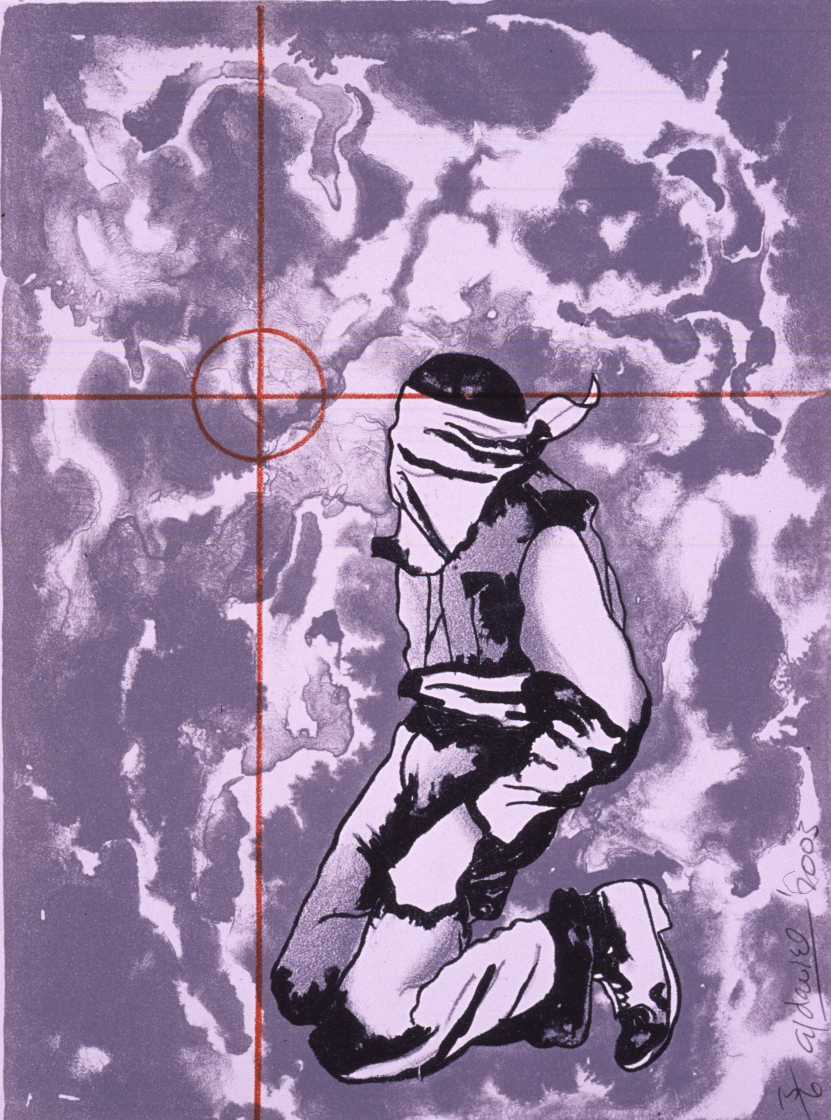

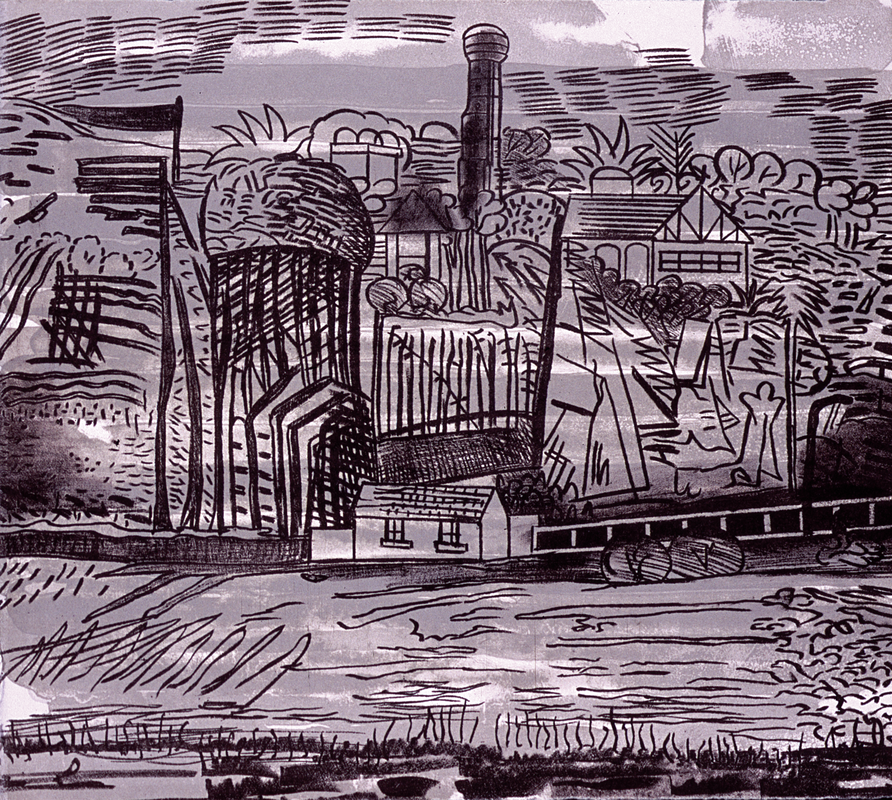

Davies had previously explored the idea of a background similar to camouflage in Operation Legitimate Target of 2003 where it had a more descriptive purpose linked to the militaristic theme. The figures of violators and victims were drawn on stone with lithographic crayons and inked up in black, while washes of tusche on a second lithographic stone created a marbled effect that picks up on the patterns of combat uniforms, printed in purplish-grey tones and muted red. Tusche washes are used to quite different effect in the monochromatic lithographs entitled Twin Towers, Wanganui (2003-04). Here the tones suggest mistiness from the river and atmospheric perspective, particularly because Davies has favoured greys, blues or sepias for the washes, calling to mind the fluid watercolours of generations of British landscape artists. Like them, too, he uses the washes to set the mood of his scenes, with deeper, denser applications invoking the intensity of a threatening storm.

Davies had previously explored the idea of a background similar to camouflage in Operation Legitimate Target of 2003 where it had a more descriptive purpose linked to the militaristic theme. The figures of violators and victims were drawn on stone with lithographic crayons and inked up in black, while washes of tusche on a second lithographic stone created a marbled effect that picks up on the patterns of combat uniforms, printed in purplish-grey tones and muted red. Tusche washes are used to quite different effect in the monochromatic lithographs entitled Twin Towers, Wanganui (2003-04). Here the tones suggest mistiness from the river and atmospheric perspective, particularly because Davies has favoured greys, blues or sepias for the washes, calling to mind the fluid watercolours of generations of British landscape artists. Like them, too, he uses the washes to set the mood of his scenes, with deeper, denser applications invoking the intensity of a threatening storm.

Against these tonal backdrops Davies has inscribed well-known Wanganui motifs – landmark architectural forms interspersed with the quirky fantasy images of a children’s park. The drawings operate in a different register from the vaporous grounds, but are integrated with them because they are inked in darker tones of the same colour. They are also unified by an apparent freedom of mark making which belies the complexity of the processes for printing up lithographs. Paralleling the loose painterliness of the tusche washes, Davies’ imagery has taken full advantage of the permissive directness of drawing onto lithographic stones. He produces freely drawn representations with irreverent contours, ranging from uninhibited scribbles to the precisely ruled lines which demarcate whimsical details like repetitive brickwork, both suggesting the freshness yet concentrated attention of a child’s drawing.

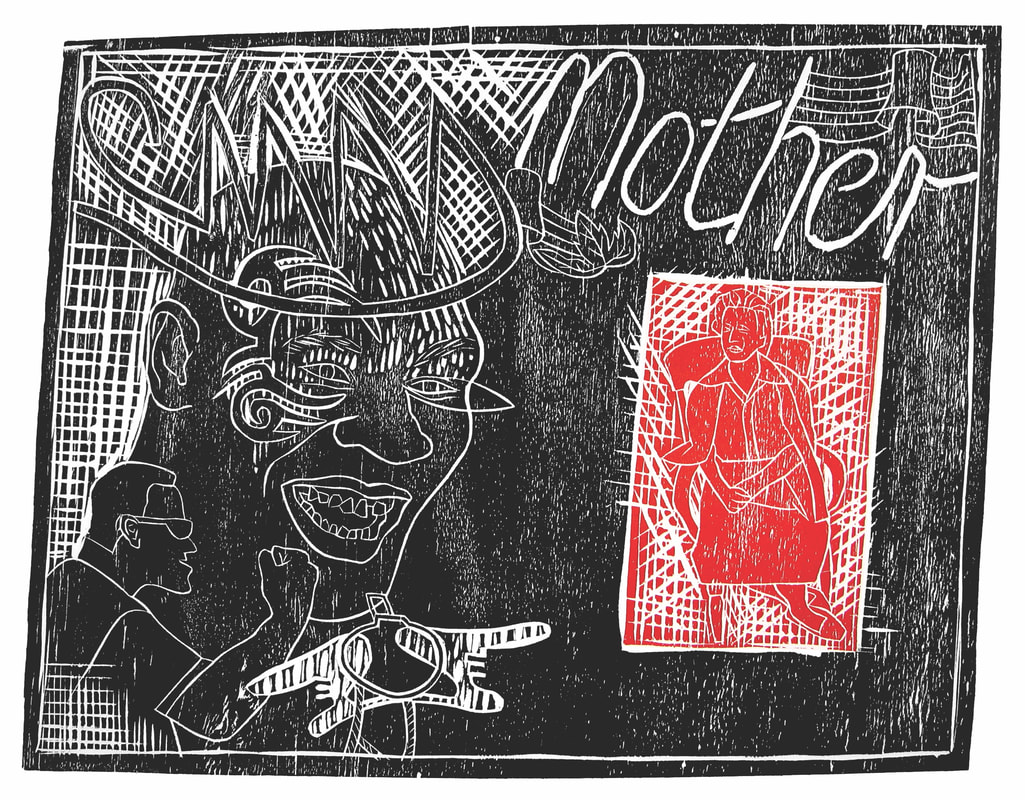

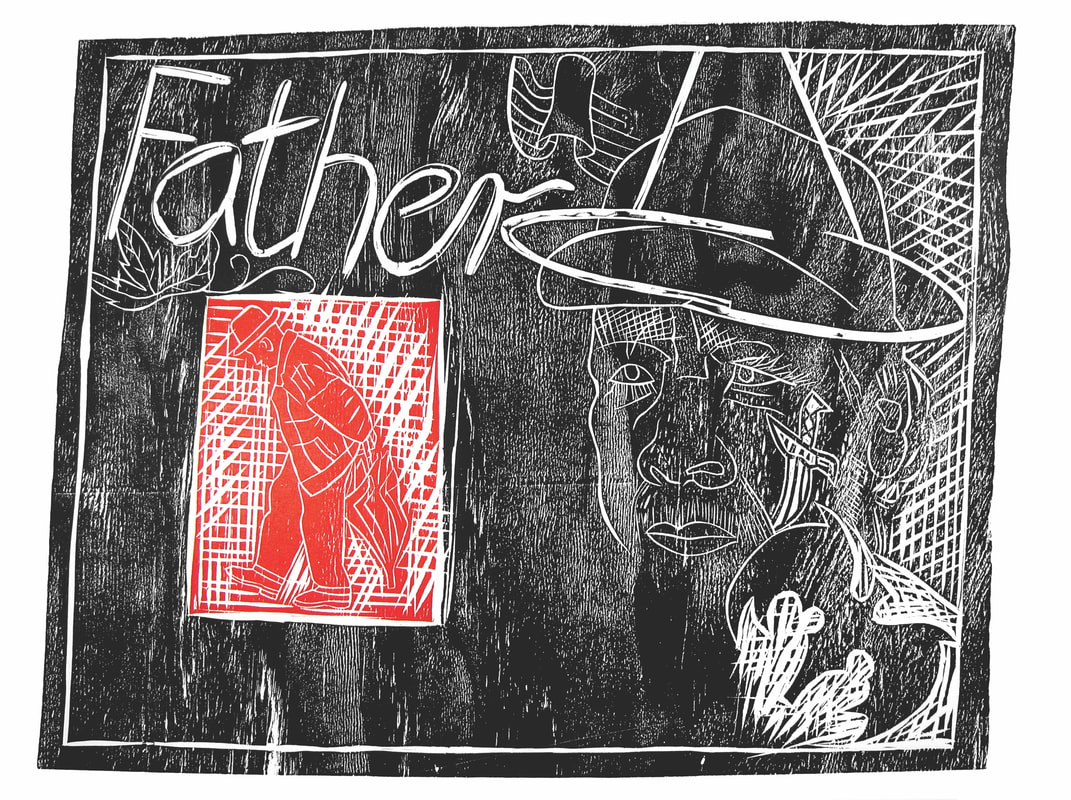

Davies also relied strongly on line in a recent series of woodcuts, Crossroads–A Family Portrait (2005-06). Working on a thin ply, Davies has drawn straight into the wood, cutting with a scalpel to achieve sharp definition. Although this process is less free than lithographic drawing, requiring a steady hand and firm pressure, the flowing contours appear to share the same sense of directness. Yet closer consideration shows some intricate decision making: many of the contours are not the straightforward white line that is the simplest form of relief printing. To clarify the outlines defining the larger figures on the grainy black-inked block, Davies has deployed an idiosyncratic double form of reverse cutting. In Funeral Cortège and Young Hoon, for example, he has not simply drawn the boundary of forms, nor removed areas of wood to create white silhouettes, but cut away on both sides of contours so that there is a distinctive doubling of white line – perhaps better described as a black contour outlined in white. In other prints he uses simpler lines, some assertively bold and thick, some delicately fine, such as those used for the larger heads and inscriptions of Mother and Father. Added cross-hatching sets up a textural counterpoint to the insistent grain of the plywood and its sometimes splintering surfaces.

Davies also relied strongly on line in a recent series of woodcuts, Crossroads–A Family Portrait (2005-06). Working on a thin ply, Davies has drawn straight into the wood, cutting with a scalpel to achieve sharp definition. Although this process is less free than lithographic drawing, requiring a steady hand and firm pressure, the flowing contours appear to share the same sense of directness. Yet closer consideration shows some intricate decision making: many of the contours are not the straightforward white line that is the simplest form of relief printing. To clarify the outlines defining the larger figures on the grainy black-inked block, Davies has deployed an idiosyncratic double form of reverse cutting. In Funeral Cortège and Young Hoon, for example, he has not simply drawn the boundary of forms, nor removed areas of wood to create white silhouettes, but cut away on both sides of contours so that there is a distinctive doubling of white line – perhaps better described as a black contour outlined in white. In other prints he uses simpler lines, some assertively bold and thick, some delicately fine, such as those used for the larger heads and inscriptions of Mother and Father. Added cross-hatching sets up a textural counterpoint to the insistent grain of the plywood and its sometimes splintering surfaces.

Embedded in each of the black-and-white prints is an inset with smaller motifs in line-cutting that has been inked up in red – a variant of jigsaw relief prints, although the additional block has not been used in the traditional way as a device to add descriptive colour to a single unified image. The shapes are independent fields, straight-sided but irregular in form, and their relationship to the larger format is unstable although always contained within its borders. Sometimes they read like openings of doors or windows into neighbouring spaces, sometimes like rectilinear ‘thought bubbles’ from the adjacent heads, the juxtaposition setting up a teasing relationship between the different images.

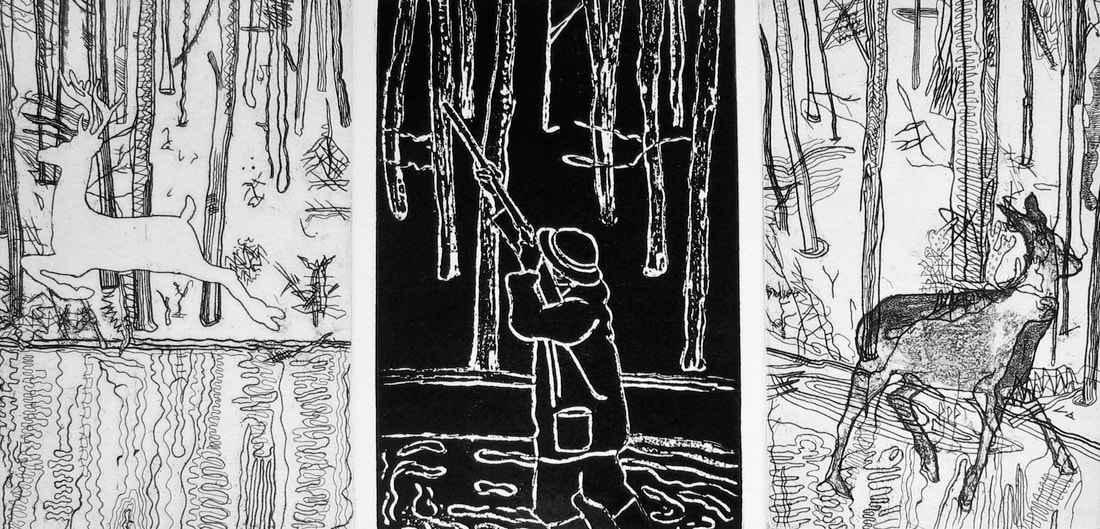

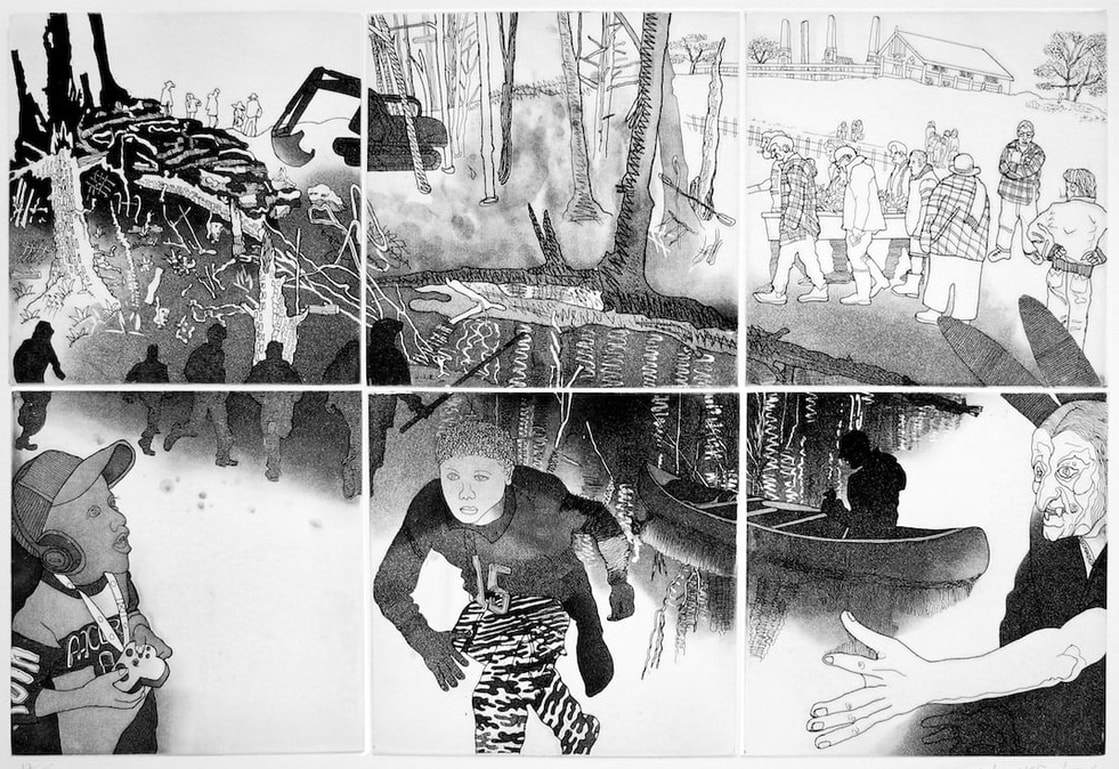

The idea of multiple plates is taken up again in Davies’ recent series, The Ballad of Brunswick Park, although here their rectilinear balance and the use of etching in ‘pure’ black and white suggest that he has reverted to a more conventional printmaking approach. This is not Davies’ first use of etching in New Zealand. To comment on the widely reported story of Kaimanawa Horses (2000) he had also chosen this genre. In that series he worked almost entirely in aquatint to create tonal images that seemed to suggest both something of the quality of grainy media photographs and a dissolution of form that alludes to the liminal existence of the wretched animals. For Brunswick Park aquatint is also employed but it plays second lead to the protagonist linework.

The first series of eight prints (1-8), depicting hunting scenes and animals both wild and domestic, was created in triple format – three vertical plates combined to create a landscape format. The plates that make up each of these prints are independently treated, but not unrelated to each other. There is the commonality of subject matter of course, sometimes also including a continuous horizon line or river bank, or a consistent setting defined by tree trunks. But more significantly the prints share a similar form of mark making that both differentiates individual panels and convincingly draws the series together. Sometimes Davies uses a fine line that has the constancy of an unbroken contour to define one of the creatures, or that creates repetitive marks to suggest textures on tree trunks and calligraphic scribbles the reflective ripples of water. Sometimes he deploys the thicker, more grainy delineation of sugar lift, which lends itself to infilling with both the subtle tones accomplished with processing his plate in an aquatint box and the coarser granular markings achieved when he applied aquatint by hand through muslin. Breaking decisively with the lightness of these images, the central plate in four of the works has been rolled up as a relief, reversing the language of delicate lines and subtle tones in the intaglio prints, to make a bold statement of white contours on a solid black ground.

The idea of multiple plates is taken up again in Davies’ recent series, The Ballad of Brunswick Park, although here their rectilinear balance and the use of etching in ‘pure’ black and white suggest that he has reverted to a more conventional printmaking approach. This is not Davies’ first use of etching in New Zealand. To comment on the widely reported story of Kaimanawa Horses (2000) he had also chosen this genre. In that series he worked almost entirely in aquatint to create tonal images that seemed to suggest both something of the quality of grainy media photographs and a dissolution of form that alludes to the liminal existence of the wretched animals. For Brunswick Park aquatint is also employed but it plays second lead to the protagonist linework.

The first series of eight prints (1-8), depicting hunting scenes and animals both wild and domestic, was created in triple format – three vertical plates combined to create a landscape format. The plates that make up each of these prints are independently treated, but not unrelated to each other. There is the commonality of subject matter of course, sometimes also including a continuous horizon line or river bank, or a consistent setting defined by tree trunks. But more significantly the prints share a similar form of mark making that both differentiates individual panels and convincingly draws the series together. Sometimes Davies uses a fine line that has the constancy of an unbroken contour to define one of the creatures, or that creates repetitive marks to suggest textures on tree trunks and calligraphic scribbles the reflective ripples of water. Sometimes he deploys the thicker, more grainy delineation of sugar lift, which lends itself to infilling with both the subtle tones accomplished with processing his plate in an aquatint box and the coarser granular markings achieved when he applied aquatint by hand through muslin. Breaking decisively with the lightness of these images, the central plate in four of the works has been rolled up as a relief, reversing the language of delicate lines and subtle tones in the intaglio prints, to make a bold statement of white contours on a solid black ground.

This series makes explicit the manner of its making, and the primacy of linework: images that are created with contour alone reserve their forms as pure silhouettes, a number of them unsullied by any details, while tonal representations which imply more palpable form seem curiously transparent because we can read the linework of the landscape through them, revealing the sequence of production and that line preceded aquatint application. The strategy serves to integrate hunters and animals with their environment – perhaps another reference to the concept of camouflage that has intrigued Davies. But it also invites us to read process as well as form and reminds us always that, however much the subject matter implies the existence of volumes occupying space, these forms are no more than a membrane of ink on a planographic paper surface.

The first four works in the second series titled The Ballad of Brunswick Park I-VIII are six-part prints but, despite their complex division, they are more unified in their presentation than the triple prints of the earlier series. The composition is continuous: the works were initially drawn as a single uninterrupted scene, even though designed with an awareness of the compositional form of each individual plate within the whole. In II, for example, the central vessel on the water is dissected by the gaps between the plates but is a presence in all six, its dark silhouette linking the separate square plates. It forms a stabilising horizontal amidst scattered figures in the expansive landscape, some engaged in recreational outdoor pursuits, others seemingly caught up in unsettling social events. The individual images seem familiar, culled from Davies’ clippings of press stories and photographs, but the combinations are disturbing – not only because of what they represent but the way they are represented. The devices of illusion are used as subversive agents to confuse the eye – a foreshortened arm that does not fit the adjacent figure; shadows cast by forms that are absent; changes of scale that do not denote recession. The tonal treatment of figures on the left endows them with tangible volume, while most of those to the right are defined only by sparse linework. Yet one of those linear figures who trudges into the distance evokes solid ground to be traversed, even though there are no identifiable visual clues to give it substance on the vacant white paper, and the implied ground plane fuses with the continuity of the river setting, which is endowed with identifiable physical form in its shimmering surfaces. There is no ‘comfort zone’ for easy viewing: the eye is constantly challenged by perplexing visual conundrums.

The first four works in the second series titled The Ballad of Brunswick Park I-VIII are six-part prints but, despite their complex division, they are more unified in their presentation than the triple prints of the earlier series. The composition is continuous: the works were initially drawn as a single uninterrupted scene, even though designed with an awareness of the compositional form of each individual plate within the whole. In II, for example, the central vessel on the water is dissected by the gaps between the plates but is a presence in all six, its dark silhouette linking the separate square plates. It forms a stabilising horizontal amidst scattered figures in the expansive landscape, some engaged in recreational outdoor pursuits, others seemingly caught up in unsettling social events. The individual images seem familiar, culled from Davies’ clippings of press stories and photographs, but the combinations are disturbing – not only because of what they represent but the way they are represented. The devices of illusion are used as subversive agents to confuse the eye – a foreshortened arm that does not fit the adjacent figure; shadows cast by forms that are absent; changes of scale that do not denote recession. The tonal treatment of figures on the left endows them with tangible volume, while most of those to the right are defined only by sparse linework. Yet one of those linear figures who trudges into the distance evokes solid ground to be traversed, even though there are no identifiable visual clues to give it substance on the vacant white paper, and the implied ground plane fuses with the continuity of the river setting, which is endowed with identifiable physical form in its shimmering surfaces. There is no ‘comfort zone’ for easy viewing: the eye is constantly challenged by perplexing visual conundrums.

It is hardly surprising then to learn from Davies that his etchings are highly considered constructs. He begins with drawings on tracing paper, transferred onto the smoked surface of his zinc plates, but they are endlessly redefined and redrawn as he seeks out the line that will match his purpose. There are sequences of acid biting too, with carefully calculated nitric acid mixes and precise timing. Drawing may be redone yet again after the initial bite, and after proofing, areas stopped out with shellac and reworked. Tone is always in his mind as he draws, but is another stage in the process, which may be achieved by the finest dusting of surfaces in an aquatint box, or with more spontaneous applications by hand.

The final four prints in The Ballad of Brunswick Park are still in production as I write, large single plates this time. While this may sound reassuringly traditional, knowledge of Davies’ practice leads us to expect that he will find ways to disrupt a straightforward reception of his images. We can also confidently anticipate that this will depend as much on the processes he deploys as on the subject matter he depicts. Davies may not have broken with the time-honoured techniques of printmaking, but they are far from traditional in their application. In his prints, line, tone and colour are proactive signifiers independent of representation. Whether Davies’ multiple matrices are restricted to the parameters of a single medium, or extend to multiple processes, compound plates and overprinting further complicate structure and composition. The different registers of print language that he employs engage viewers, not only with the images he represents and the narratives he constructs, but with the discourses of printmaking.

The final four prints in The Ballad of Brunswick Park are still in production as I write, large single plates this time. While this may sound reassuringly traditional, knowledge of Davies’ practice leads us to expect that he will find ways to disrupt a straightforward reception of his images. We can also confidently anticipate that this will depend as much on the processes he deploys as on the subject matter he depicts. Davies may not have broken with the time-honoured techniques of printmaking, but they are far from traditional in their application. In his prints, line, tone and colour are proactive signifiers independent of representation. Whether Davies’ multiple matrices are restricted to the parameters of a single medium, or extend to multiple processes, compound plates and overprinting further complicate structure and composition. The different registers of print language that he employs engage viewers, not only with the images he represents and the narratives he constructs, but with the discourses of printmaking.